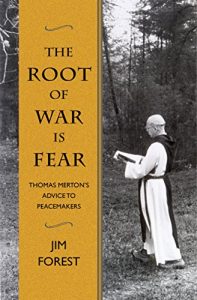

The Root of War is Fear: Thomas Merton’s Advice to Peacemakers by Jim Forest

The Root of War is Fear: Thomas Merton’s Advice to Peacemakers by Jim Forest

Reviewed by David Lorimer

In the final chapter of this powerful and inspiring book, Jim Forest, himself a lifelong peacemaker who met Thomas Merton as a young man, comments that ‘we now find ourselves in a state of fear driven permanent war’, enacting the agenda of a Project for a New American Century with its mantra of the war on terror as a way of driving arms-driven economies fomenting conflict around the world – depressingly, the arms companies overwhelmingly supported Hillary Clinton in the recent US presidential election. If you carry on making weapons – and I understand that the US is currently developing smarter, smaller nuclear arms – they have to be used, otherwise there is no need to produce any more and, it is argued, the arms industry is key to exports (and employment) not only in the US, but also in the UK and France. Clinton was involved in the record-breaking $80 billion arms deal with Saudi Arabia and seemingly quid pro quo donations to the Clinton Foundation. Such systemic and widespread corruption is rather discouraging.

Had Thomas Merton been alive now, he would have been a vociferous critic of the climate of fear that continues to be manufactured by the media. The title of this book corresponds to an essay he wrote in the early 1960s, at the height of the Cold War. One of the great ironies is that what Merton was arguing in 1962, and for which he was censored, had become by 1965 the official policy of the Catholic Church. He remarks that Pope John XXIII would not have got past the censors if he had not been Pope – and Pope Francis is a worthy successor in that respect. Jim tells us that two of the Americans the Pope most admired, besides Lincoln and Martin Luther King are Merton and Dorothy Day.

Throughout the book, Merton’s emphasis is on being true to gospel of love in the New Testament and correspondingly sceptical of mealy-mouthed compromises justifying violence, especially while not recognising our own complicity. He writes that ‘men have become objects not persons. Now you complain because there is a war, but war is the proper state for a world in which men are a series of numbered bodies. War is the state that now perfectly fits your philosophy of life: you deserve the war for believing the things you believe. Insofar as I tend to believe those same things and act according to such lies, I am part of the complex of responsibilities for the war too.’ (p. 9) Paradoxically, we arm ourselves in order to avoid war and preserve peace, but make enemies in the process so that war becomes unavoidable. Merton is very clear that the only winner in war is war itself. Moreover, this is an externalisation of our thoughts and desires, so if we want a new world, we have to change our predominant thoughts and desires, crucially cultivating a climate of love and trust in order to overcome the prevalent climate of fear.

All this led Merton to embrace nonviolent action. He could not stand by passively and fatalistically, and this created a huge tension with the authorities tried to gag him by arguing that he would make a much better contribution simply through prayer and monastic life. He refuses an ideology of matter, power, quantity, movement, activism and force, embracing instead a ‘life that is essentially non-assertive, non-violent, a life of humility and peace’ as a statement of his position. He felt that adopting such an attitude ‘implies no heroism, no extraordinary insight, no special moral qualities, and no unusual intelligence (p. 93), but it does mean embracing the Sermon on the Mount, a way of forgiveness and non-retaliation, which Christians throughout the ages have found so difficult to practise.

I liked the development of the word peacemaker rather than pacifist, as the former implies an active approach of embodying peace and renouncing violence in our own thinking and feeling. At the time the Vietnam, Merton felt that ‘our external violence in Vietnam is rooted in an inner violence which simply ignores the human reality of those whom we claim to be helping’ (p. 169) – a point graphically illustrated in a photo immediately beneath this quotation. Fascinatingly, he had a deep encounter with Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese monk, at around this time ‘he is more my brother than many nearer to me in race and nationality, because he and I see things in exactly the same way.’ (p. 163)

All of this is a powerful message for our own time and a reminder of the importance of living the law of love in our own everyday lives where it is so easy to become caught up in responding to the pervasive climate of fear and violence. I was struck by a passage where Merton writes that the validity of the Church depends precisely on ‘spiritual renewal, uninterrupted, continuous, and deep’. (p. 56) This means listening to the voice of conscience rather than external authority, pursuing our work ‘not on the results but on the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself.’ Such was the advice given by Merton to the young Jim Forest and from which we ourselves may take heart. Our individual contributions may be small, but they are significant in that it is only we ourselves, working with other like-minded people, who can make them. As Rowan Williams comments, ‘Merton’s witness for peace is more urgent than ever in a world becoming rapidly more insane and feverishly impatient.’