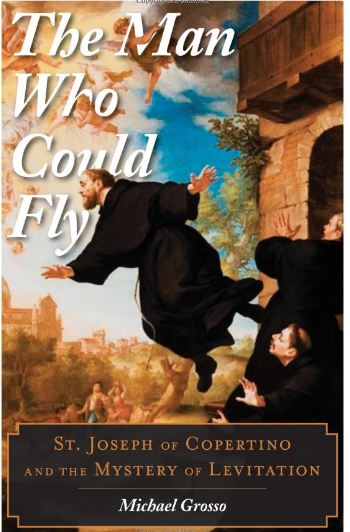

The Man Who Could Fly: St. Joseph of Copertino and the Mystery of Levitation by Michael Grosso

The Man Who Could Fly: St. Joseph of Copertino and the Mystery of Levitation by Michael Grosso

Reviewed by Nicholas Colloff

A miracle, to quote St. Augustine, “does not occur contrary to nature, but contrary to what we know of nature.” So what happens when a miracle occurs, repeatedly, what can it tell us about the nature of the nature we inhabit and, more importantly perhaps, about its meaning?

This is the subject of Michael Grosso’s searching, beautifully written and challenging book. The repeated miracle in question is a seventeenth century Franciscan priest’s ability to levitate, not once or twice, but repeatedly over years, observed by hundreds of people, many of whom originally were sceptical. These repeat performances, accompanied by other manifestations of psychic skill, were an embarrassment to the Church not, interestingly, for their plausibility (after all St Joseph was not the first flying religious) but for the temptations of pride and self-advertisement in which Fr Joseph might become ensnared. For this reason, he was investigated more than once by the Inquisition, always being exonerated but always presenting a difficulty to the Church hierarchy who forced him into ever more remote priories until he spent the last period of his life virtually a prisoner in a single room. It is ironic or perhaps emblematic that establishments of all kinds find anomalous experience difficult (though for different reasons). This inquisitorial interest, however, is a boon to subsequent researchers given their scrupulous bureaucratic attention to detail.

Needless to say our still established scientific materialism too finds St Joseph’s experience confounding so it must be a consequence of a known mechanism – mass hysteria or conscious fraud, say. Grosso patiently sifts the evidence, weighing it carefully in the balance, and leaves you with no other truly reasonable conclusion than that St Joseph could indeed, under particular and described circumstances, levitate. It would be erroneous to think of this as ‘defying gravity’ as Grosso argues as if the ‘the laws of physics’ were legislative rather than the best possible available descriptions of what can be taken to be the case. If Joseph can fly, the question now is how – what force or dynamic can act in certain contexts such that the ‘normal’ rules of gravity are transformed? What might that look like and how does it effect how we think about the nature we inhabit?

The first thing it asks us is to revisit is the relationship between mind and matter (and indeed whether those neatly divided categories are not grossly misleading). For Joseph’s ability to levitate was connected with the achievement of certain, circumscribed patterns of ecstasy when, forgetting himself, all his concentration was on the religious trigger of his intense devotion. Our minds appear not simply to be contained epiphenomena of our material brains but causally effective. Grosso takes us through a graded ascent of those abilities – from everyday intentionality through to levitation – in order to make the case for their plausibility – differences in degree and commonality but not of kind.

If this be so, where might we go to discover what the eminent physicist and early explorer of the ‘paranormal’, Sir William Crookes, called, ‘a psychic force’ by which under certain conditions and, within as yet unknown boundaries, a person with ‘a special nerve organisation’ can enable action at a distance, without muscular effort shift objects or, in the case of St Joseph, levitate? Has our understanding of consciousness and matter advanced since Crookes’ nineteenth century speculation grounded in observed phenomena? Yes, argues Grosso, if slowly, because with the development of quantum mechanics, consciousness has undertaken ‘a return of the repressed’ rather than being seen as a quirky (and limited) epiphenomena, it is becoming potentially a constitutive, structuring reality that permeates everywhere. In his penultimate chapter, Grosso explores a number of approaches to mind in quantum mechanics that are a suggestive basis for a renewed interest in consciousness as a non-local, unifying reality that transcends and configures ‘matter’. We are reminded that if the world is seriously strange at the quantum level, why stop there?

If this is so, what might it mean? The final section of the book turns to what Grosso describes as a parapsychology of religion. I recall attending a science and religion conference many years ago and being embarrassed to find myself the only empiricist there. All the conversation was on whether religion and science in their most abstracted forms were or were not compatible not on the ground where they might actually meet which, as Grosso articulates, is in the space of the ‘psychic’ where the study of the paranormal begins to extend and deepen our understanding of human possibility.

This parapsychology of religion will not simply confirm the ‘realities’ confessed to by any particular religion; indeed, they might be as challenging to them as they are to ‘mainstream’ science, but they offer a fruitful path through the thicket of incompatible claims to the normative. In a modest yet compelling way Grosso sketches how this might be so in reinforcing the belief in a spiritual world, a belief in the power of belief itself, in the power of prayer, in a life after death and in miracles. It advances William James’ request in his ‘Pluralistic Universe’ to put empiricism at the heart of religion once more such that, “a new era of religion as well as philosophy might begin,” one that experiments after the truth, modest, wondering, humble as befits the temperament of a saint who could fly yet placed all his emphasis on the devoted, experienced love that at its heart triggered it.

“The Man who could Fly” is not only an exemplary case study of a levitating saint but an agenda both for further research, search and reconfiguration of what it might mean to be human in a universe the knowledge of which remains enticingly and enjoyably uncertain, open and inviting.