By Paul Kieniewicz

Back in the 1960’s, the Polish Science Fiction writer, Stanisław Lem wrote a short story about robots. A rocket along with its calculator lands on an uninhabited planet and subsequently spawns a race of robots. The robots (who call themselves Magnificans), build an entire city along with theatre and music ensembles. Along with their leader, worshipped as “His Inductivitee, The First Calculator”, they are filled with a total hatred for the human race, and everything human (which they call, gookumkind). People whom they call Mucilids, are portrayed as oppressors, who force Magnificans into slavery, punish them arbitrarily by putting sand into their joints and feed them rancid oil. Nowhere is the hatred for humans better displayed than in the robots’ brochure on How to Recognize a Mucilid.

The upper part of a mucilid moves along with a process called breathing. Check to see if the hand is doughy. From its mouth opening there’s a slight breeze. Finally, the mucilid emits a watery ooze, mainly from the forehead.

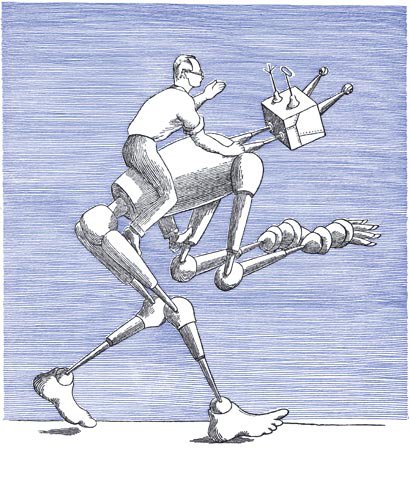

One has to wonder whether this humorous piece is actually describing the future of human- robotic relationships. It’s certainly a relevant subject given the amount of research these days into making robots and other forms of AI. We’d like to have robots for sex toys, gratuitous violence, to make our minds capable of fantastic discoveries, to improve our bodies, and finally – to achieve immortality by disposing of our organic bodies and downloading our minds into an AI entity. There is even a robot that is being taught compassion, and which leads meditation sessions. In all of those schemes, one senses that Lem’s names for robots as Magnificans, and for humans, Mucilids are chillingly prescient.

The view of the human body held by many proponents of AI, is of a large head with many disposable appendages. This is because our mind is viewed of supreme importance. As for the rest of the body, it is messy. It excretes ooze and other substances (just like Mucilids), needs to be fed, it gets old and decrepit in its time, and horror of horrors — it dies! Why not replace it with a brand new shiny outfit that doesn’t rust, the Magnifican? Presumably he’ll live forever.

If abolishing the human body was not enough, how about replacing the mind too. A recent article by Ahmed Alkhateeb, published in Atlantic Monthly, suggests that we can also programme AI to do science. Our bot will then trawl through thousands of published papers, look at data, and create new hypotheses that could explain the data. Why task our brains with doing science when we can teach a machine handle data much better and faster than human beings and come up with better results? Then, when we gaze at the new theory, we can all say, “Wow!”.

This modern view is nothing new. For centuries both Eastern and Western religions have championed a dualistic view of human beings, of a pure soul trapped in a material body. The soul is subject to the body’s various humours and needs — all mostly sinful and undesirable, illusions and limitations. The more perfect condition, presumably after-death, is a disembodied state where we aren’t bothered by the body and its sensuality. A version of this view was also prevalent in some of the Mystery Schools at the beginning of the Christian Era. The disdain for the body that we see today in the AI community seems to echo the earlier, religious view. And if, after the Singularity, we can dispose of the human body altogether, and develop a super-mind, why not?

Before rushing forwards to sign up for immortality as an AI life form, it’s worth recalling what we will be giving up: our sensual existence — and that means, feeling cold, hot, appreciating music, food, the taste of bitter coffee, cigarettes, smelling the aroma of flowers, the feeling of wind on our faces and yes, also physical love and sex. It’s by no means an exhaustive list, but those are also some things that, according to theologians, the angels envy us for. In his film, Wings of Desire, Wim Wenders captures those sentiments in a conversation between Peter Falk and a disembodied angel, following which the angel decides to become mortal.

We often forget that it is because of our sensual nature that we are able to grow in consciousness, and indeed to grow spiritually. This is because our sensual nature is what makes relationship possible, with each other and with our environment. It is through doing, and through our relationships that we grow and arrive at new insights. Suffering also plays a major role in teaching us, or it may crush us. This is really why we are the envy of angels. Consider this as a thought experiment. Imagine yourself in a disembodied state. Angels (or other disembodied spirits) can observe us, love us, but they cannot take action like we do, to bring about change in themselves or in their environment. Their experiences are not sensual. This is why writers such as Thomas Aquinas proposed that angels cannot change their own nature either. Their consciousness is restricted according to their nature. Without a physical existence, they are in the position of trying to move an object with a lever, only to find that there is no fulchrum. According to this model, our capacity for new insights, for transforming our nature far exceeds that of angels, because of the our sensual nature.

Understandably, growing old is no fun, and especially when the body starts to fall apart. Then, one can relate more to Yeats’ view of being “fastened to a dying animal”, than to Walt Whitman’s praise of the body in I sing the body electric.

I sing the body electric,

The armies of those I love engirth me and I engirth them,

They will not let me off till I go with them, respond to them,

And discorrupt them, and charge them full with the charge of the soul.

Was it doubted that those who corrupt their own bodies conceal themselves?

And if those who defile the living are as bad as they who defile the dead?

And if the body does not do fully as much as the soul?

And if the body were not the soul, what is the soul?

By the way, Lem’s story ends with the protagonist’s discovery that the robot planet contains no real robots, but only human agents dressed up as robots, all sent in disguise to infiltrate the ranks of the Magnificans. Having betrayed their humanity, they all act like robots, and wage a fake war on humans. He sadly concludes that “only Man can be a bastard”.